Worldwide research is under way to develop this valuable feature.

Do you know that there’s a global quest to develop a breed of short-tailed wool sheep? Here at Team Numnuts, we’re keeping an interested eye on the new developments, including recent developments in genetic research in China and Germany. A short-tailed fine wool breed that needs neither tail docking or mulesing would bring huge economic benefits to the industry, with potential to improve animal welfare at the same time.

Now, a group of researchers claim to have bred the world’s first such sheep through a process of gene editing. It’s a fascinating story and, if a new breed can be established, one that could change the face of Australian merino farming.

Reducing tail length in sheep

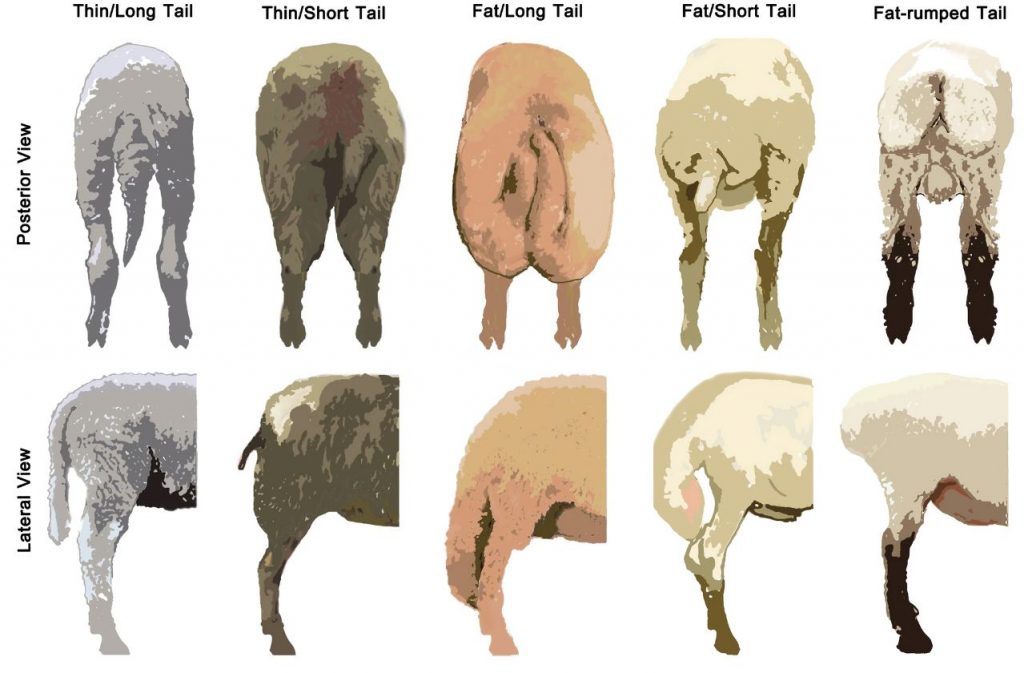

As you’ll already know, sheep are unusual amongst mammals, because rather than using their tails for balance, communication or swat flies, they use their tails and rumps to store energy as fat stores. Domestication has led to sheep breeds with different tail lengths and types to develop, including the thin or fat long tail, and thin or fat short tail.

It’s believed that primitive sheep originally had thin short tails, but when farmed in harsher territory, their tails became fatter in order to survive. Amongst these is the North European short-tailed sheep, a group of traditional breeds found in the British isles, Scandinavia, Greenland the Baltic region. For thousands of years the only sheep in these territories, they are hardy but small. There are 34 breeds in this group with a tapered short tail, a wide range of colours, and dual coated wool. These include the Finn sheep.

The Australian Finn-Merino development

Let’s look at a venture taking place right here in Australia. A decade ago, the late sheep geneticist Dr Jim Watts, The SRS Merino Company, Bowral NSW, and Merino stud breeder Don Mudford, Parkdale SRS® Merino Stud in Dubbo NSW have been using genetic selection to breed naturally short tail animals. As short tail genes don’t exist in Merinos, they have been introducing the Finnish Landrace (Finn sheep). Their aim has been a bare underside, a pencil-like shape, and sufficient muscularity for raising when urinating or defecating. [1]

Have they succeeded? In February 2021, Sheep Central reported on the first public offering of 3365 ewes and 41 rams from Parkdale SRS.

The sheep were described as having bare breeches, legs and bellies, and tails measuring a quarter to a half of the usual Merino length, eliminating the need for mulesing, tail docking and fly treatments.

Additionally, they produced a 19/20 micron fleece, and are said to have inherited the amazing fecundity of the Finn sheep. [2]

The Finn sheep has been exported around the world and crossbred with local sheep to create new, synthetic breeds. However, these are generally meat sheep, so this adapted Merino represents something of a breakthrough.

The Chinese research into short tails

In research published earlier in 2022, Chinese scientists analysed the genomics of Pamir argali, Tibetan sheep and their hybrids.

The Pamir argali breed of Mongolia became known as the Marco Polo sheep, after the famous explorer was the first to write about it in the 13th century.

It is the largest living wild sheep, with mature rams standing at up to 1.25m at the shoulder and weighing over 140 kg. Their horns can be an astounding 1.8 metres long.

Today, the breed is found in Uzbekistan, Siberia, Mongolia, the Tibetan Plateau, northern China, India and Pakistan.

The Chinese scientists announced that they had produced the short-tailed fine-wool sheep, the first of its kind globally, through gene editing. Their findings were published in an article in the journal Genome Research. At present, there are no photos of the new sheep, or news on how the short-tailed trait is passed on through reproduction. [3]

The German short tail research

Since the Chinese announcement, a group of scientists from Germany have also reported on their research for the tail-length gene. Their goal is to use targeted breeding to create short-tailed versions of normally long-tailed breeds, such as the Merino. They compared the genomes of Merinolandschaf lambs, which have a variable tail length, with those of various long and short-tailed sheep breeds and wild sheep subspecies. [4]

Where to next?

When it comes to new breeds, it’s still a long way and many years from early findings in the genetics lab to the farm. The proof will be in the paddock, so to speak. This goes beyond whether the trait can be consistently reproduced, to the questions of what might come with it in terms of health and resilience. Australia’s differing terrains and current variable weather patterns only serve to highlight this point.

Until then, our recommendation is to continue using Numnuts with NumOcaine when tail docking your lambs!

References

[1] https://www.moffittsfarm.com.au/2013/05/05/making-short-tail-merinos-a-genetic-option/

[2] https://www.sheepcentral.com/short-tailed-merino-ewes-were-the-buy-of-the-day-at-parkdale/

[3] Xin et al. Genomic analyses of Pamir argali, Tibetan sheep, and their hybrids provide insights into chromosome evolution, phenotypic variation, and germplasm innovation. Genome Res. Published in Advance. Aug 10,2022. doi:10.1101/gr.276769.122

[4] Lagler et al. Fine-mapping and identification of candidate causal genes for tail length in the Merinolandschaf breed. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):918.

[5] Kalds et al. Genetics of the phenotypic evolution in sheep: a molecular look at diversity-driving genes. Genet Sel Evol. 2022;54;61.